HST & Friends

About HST

+ Who is HST?Biographies

+ E. Jean Carroll+ William McKeen

+ P. Paul Perry

+ Peter O. Whitmer

Interviews

Media Treatments

HST's Friends

New Times Interview

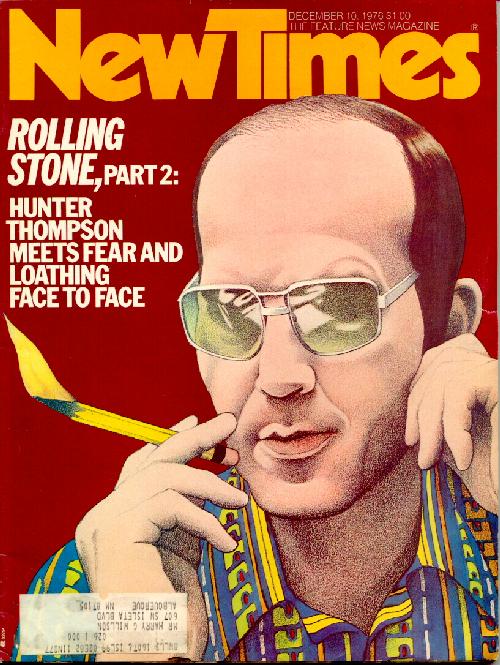

Click cover for larger

Click for Jann Wenner cover

I nearly flipped when these magazines arrived! The HST cover looked much better in person then in the scan the guy had, although unfortunately there is this little tear midway down the left side. But what could I expect from a December 10, 1976 issue?

Robert Sam Anson wrote a lengthy, two part story about Rolling Stone, and it is quite entertaining, something of a small scale version of Robert Draper's book. Anson has a peculiar style of writing as well - he uses tons of semi-colons! All the same, I'll get some more of this article typed up, since it covers the super secret "meeting of the minds" in Elko that HST hinted at in Songs of the Doomed

Original this section was in four parts that is not reflective of the original article, but I see no reason to keep it that way anymore.

Jann Wenner was freaked.

Not worried or upset in the ordinary way his editors had become used to, but freaked. Here it was, 1970, and, to believe the notices he was getting in the straight press, Rolling Stone was at the very height of its fame, the readers and advertisers almost pouring in. His money problems had been solved, his enemies vanquished. From the look of it, everything seemed golden. Only Wenner knew better. Something was wrong. Rolling Stone was reading - and feeling - a little flat.

The problem, in a word, was music. It was a puzzling phenomenon. Superficially, the music business had never been healthier. More records were being produced, more groups were being formed, "spreading more pro-life propaganda" as Wenner once put it, more than ever before. But something important was missing. Giants, some said: incontestably, there were fewer to be found. Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin were burnt out cases, not long for the world. Dylan had gone into one of his periodic funks. The Rolling Stones, bogged down with tax problems, and with Altamont still fresh in their minds, rarely appeared in concert anymore. As for the Beatles, their reincarnation was a promoter's fantasy. And the music, too, had changed. Less inventive, Wenner's own reviewers were saying: more content to repeat proven patterns.

And why not: The audience had never been bigger. Elvis had come to Vegas. The frug had invaded the White House. With the dawning of the seventies, there seemed no hamlet, however small, that could not support a top-forty station; no gathering, however chic, that did not throb to the beat of the music. Rock and roll had exploded. No longer was it the refuge of the young and the rebellious. Now it belonged to everyone.

And that, of course, was precisely the trouble. By its nature, the music was supposed to be alien and threatening. Rock and roll belonged to young people. It was their medium, their only medium, as Wenner kept saying through the sixties. But now the sixties were over. The protesters were headed for law school. The culture had cooled off. Rolling Stone, so dependent on music for its energy, desperately had to find a new gig.

And then, one memorable Friday afternoon, he walked in. The Solution.

Wenner had been warned in advance that the man he was about

to meet was a bit "out of the ordinary," as one of his

editors gently put it. But he was altogether unprepared for

the apparition who appeared that Friday and proceeded to

tell him with bizarre if utter certainty that he was about

to be elected sheriff of Aspen, Colorado. It was not just

what he said, or the way he said it, or the way he was

dressed (tennis shoes and white chinos topped by a loud

Mexican shirt), or the six-pack of beer he had brought along

(and amidst numerous belches, consumed in the next two

hours), or even the gray woman's wig he was wearing; it was

simply everything taken together, the entire weird persona,

that overwhelmed Wenner. When, at length, his visitor

excused himself to make use of the facilities, Wenner, who

had been gradually slinking beneath his desk, straightened

up, took a deep breath, turned to John Lombardi and said:

"I know I'm supposed to be the spokesman for the

counterculture and all that, but what the fuck is this?"

.

.

.

...Indeed, when he took the wig off, Thompson even looked straight: short-haired, balding, trim, as one might expect a family man with a mortgage to pay to look. It was easy to be fooled, as Richard Nixon had been during the 1968 primary campaign in New Hampshire, when he invited Thompson along

for a ride in his car for a private, hour-long chat about their mutual passion: pro-football. Of course, when the ride

was over, and they arrived at the airport, Thompson nearly killed him by leaning over the open gas tank of Nixon's

private jet with a lighted cigarette dangling in his mouth. Not that he would have harmed Nixon on purpose. "He's

a very gentle soul," Paul Scanlon once summed it up. "When he's not working, he sits home in Woody Creek and shoots at

a tree with a .45."

But when he sat down at his typewriter, Hunter Thompson was someone else entirely. Then he became the dark Prince of Gonzo, the demon of fear and loathing, out to do rhetorical battle with the enemies of truth, justice and, as Hunter perceived it, the American way - be they Hell's Angels, Vegas hustlers, Super Bowl fans, or conniving politicians. The prose that issued forth under such conditions - along with Thompson's own accounting of the chemical substances he employed to fortify himself - led many readers to suppose that his genius lay in his madness.

Alas, the truth was that Hunter Thompson, aside from certain eccentricities (such as occasionally employing a giant-sized medical syringe to inject a pint of gin directly into his stomach), was utterly sane. The "crazy" Hunter Thompson, the "Raoul Duke" who as his official Rolling Stone biography had it, "lives with...an undetermined number of large dobermans trained to kill, in a fortified retreat somewhere in the mountains of Colorado" - was no more than a cover, an elaborate disguise devised to conceal a warm, generous, rather shy man who wanted nothing so much as to be a writer,

and concluded that great writers had to be, by their very nature, a little larger than life.

.

.

.

Sportswriting, as far as Thompson was concerned, was the perfect preparation for politics: "Sportswriters are used to being lied to...So you come in a little angry....It's a whole horrible con job, and either you accept it or you don't. I chose not to." That was Hunter's great weakness: he didn't like being lied to. His curse was to be an old-fashioned moralist, trapped in a world that, by its very immorality, constantly

threatened to destroy him.

The craziness started in Chicago at the 1968 Democratic convention. Thompson had come to cover it, as a straight reporter, and ended up being bloodied in the streets. For weeks afterward, he could not talk about the experience without crying. Yet he could never bring himself to write about it; the vision of kids being brutalized while "good Democrats" decried the "immorality" of the protestors, whirled in his head like a dervish. The violence with which he wrote was his only self-defence. He lived with a sense of doom, a conviction that he should never have lived past 30, and that he and the rest of the world were merely existing on borrowed time. To Thompson, the end was coming and his mission was to demand repentance. It was this Hunter Thompson, the preacher, the messenger from God, who, while covering the Super Bowl for Rolling Stone, would mount hotel balconies to warn unsuspecting fans of the fate that surely awaited them.

Part Two

The death of Ralph J. Gleason brought a strange change to Jann Wenner and Rolling Stone. In this part from the New Times article by Robert Sam Anson, the relationship between Jann and Hunter is explored. --Christine O

"When you saw Jann during those days," says one of his editors, "You couldn't help but remember the scene at the end of the Godfather, Part II, when Michael Corleone is sitting there, all alone, having killed all his enemies, and being able to trust no one, except family. And now, for Jann, the only family he ever knew was gone."

Or almost gone. Because there was still Hunter - only Hunter was rapidly slipping away.

At one time, the two of them had been very close, as close, at least, as Wenner got to anyone who worked for him. Wenner not only appreciated Thompson's talents, but genuinely seemed to like him as a companion. During Thompson's rare forays to San Francisco, he was a guest at Wenner's house, as was Jann at Hunter's when he came to Aspen to ski. Wenner, who had a well-developed, if cynical, sense of humor, delighted in Thompson's continual put-ons, though on some occasions they could go too far. One night, for instance, the two of them and a bartender friend of Hunter's were relaxing in the study of Jann's townhouse, listening to records, talking, and getting quite stoned on hash. Thompson wanted Wenner to listen to a Joni Mitchell album he thought deserved special praise from Rolling Stone, but Wenner had nodded off. So Thompson attracted Wenner's attention as only Hunter Thompson could, namely, by blasting him in the face with a fire extinguisher. Wenner awoke in a cloud of gray gop. It covered the room, but nothing more completely than Wenner, who stumbled out on the patio, gasping for breath. Wiping the goo from his eyes, he crashed back into the room, directly into the sliding glass doors. By the time he reached Thompson, gasping and heaving, he was so angry that he shook his fist, shouting, "It may take me the rest of my life, but so help me, I'll get even with you." With that, Hunter, who was laughing uncontrollably, blasted Wenner's dog and sent him careening out onto the patio, as a demonstration that fire extinguishers were actually quite harmless. (More recently, Thompson played the reverse of the trick on Wenner, when, one night in Wenner's New York apartment, Hunter fulfilled "the ultimate ambition every writer has about his editor," and literally breathed fire on him. The stunt, which is not recommended for the faint of heart, involved blowing a mouth-full of lighter fluid over a lighted Zippo in the direction of the intended victim, who, if he were not fast on his feet, would be engulfed in a whooshing, rolling fireball. Wenner was merely singed.)

Their friendship survived such incidents, and, for a time, the bond between them grew continually stronger. They wrote each other long letters, and talked late at night for hours on the phone, planning their adventures. Jann said that when he became president of the United States, Hunter could be his press secretary, even his secretary of state. But, for the moment, he desperately wanted him to come to San Francisco, and run the national affairs desk full time. As an inducement, he offered to buy Thompson a house and sell him a significant block of Rolling Stone stock at cut-rate prices. Thompson was intrigued, but wary. He considered Wenner to be an essentially schizoid personality. There was the "nighttime" Jann Wenner, uptight, greedy, and vindictive. His friendship was with the nighttime Wenner. He feared that by coming to San Francisco, he would, as so many others had, come face-to-face with the daytime Wenner, and grow to hate him.

Part Three

At the pinnacle of his fame and in constant demand to speak before college audiences, Thompson was finding it harder and harder to find something he wanted to write about. Politics no longer interested him. He was a form searching for a subject. The dark moments of the creative soul, when he found himself looking at a blank piece of paper in the typewriter - "down to the deadline again...and those thugs out in San Francisco will be screaming for Copy. Words! Wisdom! Gibberish! Anything! The presses roll at noon....This room reeks of failure once again..." - were becoming more and more frequent. Wenner made story proposals: Coors Beer...Cocaine. Nothing worked.

Finally Thompson tried Zaire. It seemed a natural place to look. Muhammad Ali was attempting a comeback, fighting George Foreman. The place was dark, mysterious. All the writing heavies would be there. What better spot to rekindle the Thompson magic? But there was unexplained trouble - "too much voodoo, black magic and witchcraft," he told Felton later - some sort of fiendish hex had been placed on Gonzo. Actually, what had happened was that Thompson had set out to discover were all the money was going, and had run into a curtain of silence. Then, to complicate matters, he contracted malaria. In the end, he didn't even go to fight. Didn't, in fact, write a word. Merely came home, depressed and delirious from malaria.

Wenner, though, still had hopes. Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail had worked once; there was no reason why it could not work again. He flew to Aspen with a book contract, giving Thompson a $75,000 advance against a '76 version of Campaign Trail. Everything seemed to have been worked out between them. Then, Wenner returned to San Francisco. Silence. Hunter waited for the check to arrive in the mail. A week passed. Nothing. Then another week. Finally he called Wenner, who casually informed him that he had decided to fold the book company, but had not gotten around to informing Hunter. So there would be no book. And no advance. Hunter was bouncing off the walls.

This was the end. He would not deal with that rat-fucker again. And, for months, he didn't, ignoring the letters and the phone calls that kept coming. Then, early one evening in March 1975, Hunter was watching a nightmarish film of the evacuation of Da Nang on the evening news. The phone rang, and Hunter picked it up. It was Wenner, saying, "How would you like to go to Vietnam?" Hunter couldn't resist. The collapse of the American empire was a happening tailor-made for his talents. Within days, he was heading out over the Pacific.

Part Four

He arrived in Saigon hours after Thieu's palace had been bombed and staffed by his own Air Force. For a man who lived with the conviction that the world was going to end next Monday, this was an especially ominous portent. Thompson had the sense of "walking into a death camp." This was it. He would never get out alive. As it turned out, the fate that was in store for him was even worse. Thompson discovered that, even as he was on his way to Vietnam, Wenner had taken him off retainer - in effect, fired him - and with the retainer went his staff benefits, including health and life insurance.

The cable Thompson fired off to San Francisco contained some of his most creative writing in months. "Your most recent emission of lunatic, greed-crazed instructions to me was good for a lot of laughs here in Saigon," he began. "The only round-eyes left to evacuate from Saigon now are the several hundred press people who are now trying to arrange for their own evacuation after the US embassy pulls out with the last of the fix-wing fleet and leaves the press here on their own. Needless to say, if that scenario develops it will involve a very high personal risk factor and also big green on the barrelhead for anyone who stays; and unless the one-thirties start hitting Saigon before Saturday, that is the outlook." He closed bitterly: "I want to thank you for all your help." The reply from Wenner was in character: "My many years of experience in war coverage and running military press corps, involvement in revolutions and general talent for blitzkrieg action tells me that you should make your own decision as to when to leave Saigon for a safe zone." Wenner added that no more money would be forthcoming, and advised Hunter to come home.

Hunter brooded, debating what to do. He desperately wanted to be on hand for the apocalypse. He had already envisioned the scene: he and General Giap riding into Saigon on the lead tank, Hunter drinking a beer and waving to the cheering throngs. But he was worried. For some reason, the NLF spokesman, whose favor Hunter had sought to curry, was giving off a lot of bad vibes. At every press briefing, he warned what would happen to "bogus journalists" when the revolution came to power, and, when he used the phrase, he seemed to stare right at Hunter. On the other hand, he'd be damned if he'd let the marines take him out. How could he live with it? Saigon fell today and Hunter Thompson's ass was saved by the United States Marines.... Never. Finally, he made up his mind. He got on the plane and headed for Laos, hoping to hook up with the conquerors there. Two days later Saigon fell. Hunter was stranded.

The resulting dispatch ran only two pages in Rolling Stone, by Hunter's standards a virtual note. "The paper in my notebook is limp," he reported, and the blue and white tiles of my floor are so slick with humidity that not even these white-canvas, rubber-soled basketball shoes can provide enough real traction for me to pace back and forth in the classic, high-speed style of a man caving into The Fear." It had finally happened. The mad Prince of Gonzo had met Fear and Loathing face-to-face, and it scared the hell out of him.

His friends had trouble reaching Hunter when he returned home from Saigon. He holed up in Colorado, and seldom answered the phone. Rumor drifted back to San Francisco. Cocaine, which Hunter had long scorned as a "drug for fruits," had gotten the best of him, one story went. Another had it that he finally embarked on the Big Novel that everyone knew was in him, eating at him, raging to get out. Neither was true. Hunter was merely furious at Wenner. But he would be back. Everyone at Rolling Stone was sure of that. Nothing could hold Hunter down for long.

And, briefly, he did come back, early this summer, for one, final, flailing thrust at his old enemy, the demon of American politics. But it was a different Hunter Thompson, a pale shadow of the mad-dog prince who once stalked the pages of Rolling Stone. The piece he wrote was, as always, rambling and disconnected, and, here and there, one spotted flashes of the Thompson fire (on Hubert Humphrey: "that rotten, truthless old freak...this monster, this shameful electrified corpse"). But the crazy coherence that swept a reader into Hunter's own private vision of hell was absent. Something, definitely, had changed, and nowhere was it more apparent than in Thompson's subject: a virtual endorsement of the messianic peanut farmer, Jimmy Carter.